I used to like fresh air,

When it was there.

And water. I enjoyed it,

’Till we destroyed it.

Each day the land’s diminished.

I think I’m finished.

A little Laugh-In goes a long way; but out of the maelstrom, Henry Gibson endures — an absurdist comedian lamenting social collapse in a chunky necklace, and beating Russell Brand to the punch by a few decades.

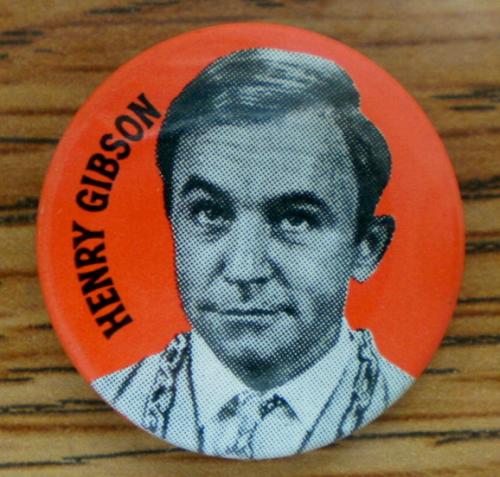

Mathematics insists that the man in the picture is in his early thirties, but like all deep thinkers worth the effort, Gibson seems an old soul already — weathered and wary. The road from spoken-word comedy on vinyl to a late-sixties Laugh-In slot on the National Babbling Company had already included three lines to Jerry Lewis in The Nutty Professor, a routine with a raccoon in The Beverly Hillbillies, and appropriating an old piece of motivational doggerel called Keep A-Goin’ on The Dick Van Dyke Show — which all seem consistent enough in age and outlook to make you idly ponder if they might be the same character, a Great Society idealist blown hopelessly off course by too much exposure to Goldie Hawn.

But even The Poet was intimidating, in his way. Henry Gibson’s comedy was the serious kind, nuggets of rock lobbed over a wall with the man himself still around the corner. One look at Robin Williams and you had a fair idea what was in his soul; the more you looked at Henry Gibson, the more he stared straight back.

Robert Altman, astute as ever, exploited this in The Long Goodbye and then enshrined it in Nashville, the film which Gibson acolytes should if possible approach in reverse.

Bone up first on the actor’s late-period elder-statesman cameos for directors with a sense of history. Work through the appearances in Joe Dante’s output — the one in Gremlins 2 doesn’t even need words, just a set of crestfallen expressions from a worker drone chewed up by capitalism, a master class in face-falling. Press Pause during The Blues Brothers to appreciate just how disconcertingly absurd the head Illinois Nazi really is — boy that Great Society stuff really went south. Warm up for the main event with his episode of Wonder Woman, a key text in live-action superheroics thanks to Gibson’s delirious 5’4” megalomaniac in purple jumpsuit and jackboots, a would-be conqueror branching out into sports management. (Gibson holds a flower for a while; the man’s characters connect like a Wold Newton family tree.) The actor affords his material the greatest respect by tearing it to shreds, the William Shatner method taken to its logical end point. In a better world, Gibson would now be voicing Ultron exactly like this.

Only then are you prepared — or rather unprepared — for Haven Hamilton, the king of Nashville and of Nashville. If you recognise the voice, the face that enters the frame in the opening minutes singing earnestly about America’s manifest destiny is even more of a shock. Nashville is all about visual characterisations — the first glimpse of Shelley Duvall remains a sight like few others, slender enough to slot between the grains of silver nitrate — but even by those standards, Haven Hamilton looks formidable; a visionary in a Nudie suit and an unwise hairpiece. The cast famously co-wrote their own songs, giving Gibson the opportunity to revisit Keep A-Goin’ (“A special old favourite”), now repurposed into a blithely conservative anthem of self-reliance. (“Tell the world you’ll be OK/And don’t forget to pray.”)

But Haven Hamilton is not blithe. He is a walking computer, judging the odds minute by minute; a king-maker, keeper of the flame. Look at this guy: steel and chromium.

Big Stan is not made of steel and chromium. Big Stan is a 2007 Rob Schneider comedy. One must walk on eggshells here, since Rob Schneider is not the Great Satan. His comedies are out of favour because they are rude, crude, and scatological. Well, so was Aristophanes. Sex comedies have a hard row to hoe in any era terrified of both sex and comedy; they deal by definition with narrow perspectives on topics where society is hopefully developing the broadest most egalitarian view possible. But for anyone who suspects that mankind sorting itself out in the bedroom would go a long way towards helping sort itself out in the boardroom, the panicky expulsion of all the dirt from popular comedy in favour of Judd Apatow’s wistful missionary-position milquetoasts tells us some uncomfortable truths. Mr Schneider puts the rabble back into Rabelais.

Big Stan plays homosexual panic for laughs, which may be all you care to know. Schneider himself plays a serial embezzler, sent to the big house for accumulated infractions, driven hysterical by the prospect of what might happen to him in the showers. There are any number of reasons why this is a limiting concept — most of its implications were already taken to the cleaners by Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell in Tango & Cash — which might be why the film tacks instead into an anti-corporate parable, in which the crooked warden envisages redevelopment of the prison site into a more lucrative mall. Tolerance, peace, love and understanding among the warring ethnic conclaves of prison-population America turns out not to be the solution, except when it is. The liveliest aspect of the film is the casting, which since Schneider directed it is presumably down to him. We’re not here to discuss David Carradine’s late career path, but Big Stan is a high water mark for his own blend of sour mash self-parody: he is The Master, a martial arts sensei dispensing aphorisms and torture from behind a cloud of cigarette smoke, leering lasciviously at a slightly embarrassed Jennifer Morrison. (The Master is impotent, if you’re marking your Male Anxiety scorecard.)

Big Stan is Henry Gibson’s last cinema film. By now aged into prime mentor material, he plays Stan’s cellmate and confident, the ex-alcoholic wife-murdering Shorts. If not quite a walk-on, it’s certainly a stroll-on; Gibson in jovial grandpa mode, first seen cross-legged on an upper bunk from a low angle, either Yoda or the Cheshire Cat. His fourth line is a masturbation joke, and thus the die is set. His longest speech is the required backstory of regret and loss — mentors need their burdens — and if by some miracle it had been able to support the weight of Gibson’s sarcastic barbs from a bar stool in Magnolia about vaguely parallel matters, well what a moment that would have been. Instead Shorts mostly lurks in the back of scenes, the traditional position of the esteemed character actor — behind and to the left. He’s a constant and largely irrelevant presence, one face among many; but the eyes are still clear, filled with conscience.

Artists rarely get to choose their last artwork, and Gibson’s final lines were not uttered in Big Stan but back on television, playing a judge on Boston Legal. A map of the actors parachuted in as judges on US legal shows would be glorious — the trunk of this mighty tree is Jeffrey Tambor’s bonkers Al Wachtel in Hill Street Blues — but in Henry Gibson’s case, history seems to be aligning behind him. Boston Legal’s high-flying liberal threnodies delivered from the bench ring all sorts of bells with the meandering fretful anxieties of The Poet delivered from behind a flower; the same wish that things were different, combined with recognition that they are not. Weathered and wary. Being a fine comic means first having a serious character, and Henry Gibson’s endures. Ain’t no law says you must die. Wipe them tears from off your eye. Give old life another try. Keep a-goin’.

Written for David Cairns’ Late Show Blogathon.

Winter Sleep, Sally Potter, Altered States, Je t'aime je t'aime

Winter Sleep, Sally Potter, Altered States, Je t'aime je t'aime