Paul Schrader’s last couple of films involved Nicolas Cage shouting and as it happens I preferred the one that Schrader vehemently disowned, but in theory First Reformed is lower key in every way—except that a fixed camera and square frame and no music and long philosophical dialogues are just as blunt a manipulation as any other. Schrader has been tending this turf of male loss-of-faith for decades, although as he himself said all of 15 years ago:

The hypothesis is that if you reduce your sensual awareness rigorously and for long enough, the inner need will explode and it will be pure because it will not have been siphoned off by easy or exploitative identification; it will have been refined and compressed to its true identity, the divine sense.

Which makes First Reformed seem like something of a culmination. As a film of ideas about doubt and aguish in a doomed world it seems hard to dismiss, partly because the ideas arrive in a ceaseless stream, agonies everywhere. A very blunt sequence in which Ethan Hawke’s tormented priest and Amanda Seyfried’s grieving widow levitate into an airborne dreamscape during a fully-clothed erotic encounter with dissonant atonal music on the soundtrack will be the make-or-break point for most people. But the helpless wails and animal growling Hawke makes when he sees Seyfried in the church at the end are dire enough to make anyone who might have some point in life have found themselves making similar noises dig their nails into the armrest in empathy and recognition, one of art’s highest goals since forever.

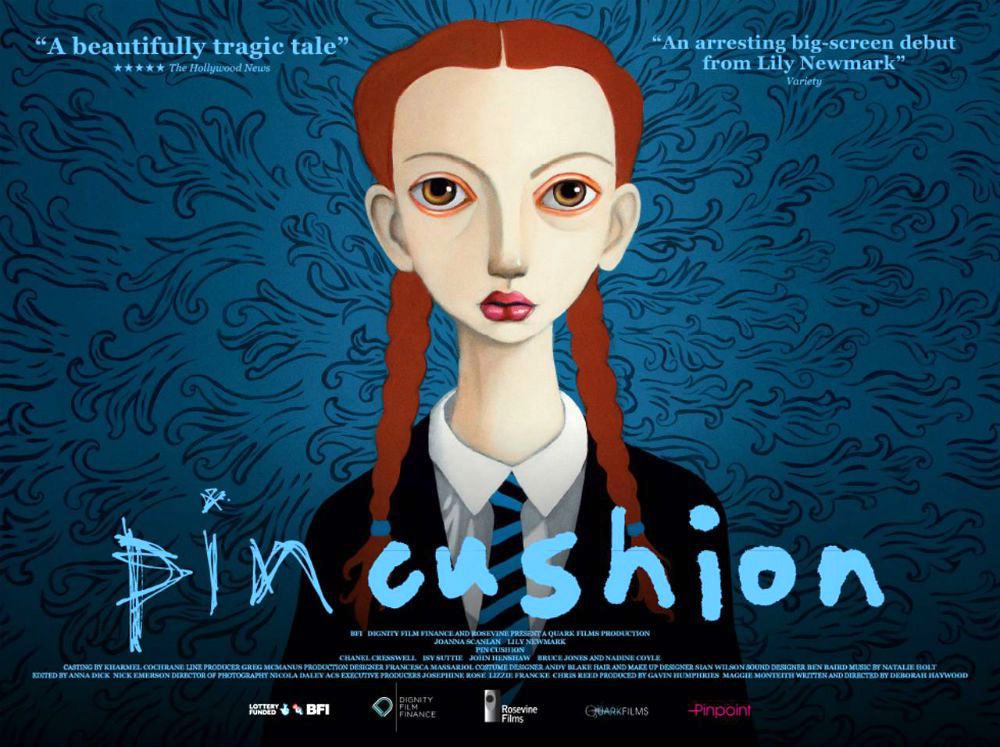

Speaking of anguished cries. At this point in time I salute any British film that doesn’t succumb to the dire siren song of realism, since the results of that only ever seem to be council estate aggro propping up the programme of domestic film festivals. Surrealism instead of realism, fine; romanticism instead of realism, double-plus fine. Pin Cushion is terrifically photographed and edited, with its creator Deborah Haywood pouring enough of her own heart towards the performers that a lot of it bounces straight back from them intact, and the framework of young girls emerging from childhood in scenarios that are at least adjacent to fairytales is eternally solid. But the methods employed are ones that a viewer will have to make their own peace with, and after due consideration I’ve decided not to give them house room.

Bullying, whether childhood or adult, is the third rail, so visceral is most people’s reaction to the sight of personal tyranny and intimidation reenacted for narrative fiction purposes, even in the fairytale bight blue Neverland of Pin Cushion. Apart from the 0.8 percent of people who had a blissful adolescence, bullying is sandpaper on the nerves of everyone. Young people have reasons to be uncomfortable watching, parents really have reasons to be uncomfortable watching, and a sane viewer is forced to vacillate between appalled recognition and the bottomless abyss of human nature. For sure these particular agonies should not be ruled out—nothing should be ruled out—as a tool for art or for artists to process their own memories and traumas and present the results, but the discomfort and crushing regrets that it conjures have to be processed and accounted for by the art, not just served up on a plate.

And in Pin Cushion that’s just the half of it, since I also reject the mother character, where Haywood strays onto the exploitation minefield. No praise too high for Joanna Scanlan, but to see her character limp on as a hunchback is to know immediately what Haywood has gone for and to question the enterprise. I get that in this oddball fairytale landscape a hunchback fits the symbolic bill, but it becomes clear not only that the character is going to have to check out so that her daughter can be reborn in a better home elsewhere, but also that Haywood is not going to allow any context for the tortures and torments of the character. The narrative manipulation by which both parent and child are lying to each other simultaneously while adrift in seas of loss and regret and torment is already close to intolerable, even before the mother reacts to her daughter’s wish to cut the cord by taking a hacksaw to her own hump. At her lowest point she sucks what is without doubt the dummy her daughter used as a baby, by which point Haywood may have ventured into the territory of mental health without due deference or balance. Either way, the character’s anguished wails and sublimated horrors of life as a misfit and the (unreliable, I suppose) information that she once wandered the streets looking to be raped like some circus freak was the point where at least one viewer lost his temper. All kudos to Haywood for making something so personal and, by BFI-funded standards, a transmission from the far ultra-violet end of the spectrum. But problematic art has to earn its authority like any other.