I took a look at The Rewrite for Critic’s Notebook, and discovered that my respect for Hugh Grant is undimmed by the fact that nothing like American Dreamz is ever coming back. At this rate neither is decent middle-age comedy, to judge by the filching of Doc Hollywood’s plot and purging of even the mild eroticism which that film used to make a point about human nature. Doc Hollywood cannot now be shown uncensored on TV in case the populace loses its mind at the sight of Julie Warner, while The Rewrite concerns a letch but is inevitably as chaste as a nun.

Another film in the homage business is ’71, judging by the ordeal Jack O’Connell’s night on the run across Belfast turns into. Welcoming a British film just because it doesn’t trip over its own shoelaces is something of a formal necessity — it doesn’t happen very often — but ’71 is stiflingly conventional, right down to its conventional reverence for the US indie sector. Somewhere in the archives is me emerging from James Marsh’s Shadow Dancer and detecting that the topic of Northern Ireland was unmistakably now safe enough to be turned into historical drama, for better or worse. Yann Demange’s ’71 drifts on the same cultural tides, washing up on the shores of very average action grammar. If the Point Break chase, editing rhythms and all, is an early statement of intent, then the late arrival of rain machines set to Monsoon for no clear reason beyond favouriting a cliché from which all life has long since fled is the capper. An embittered character actually throws his army dog tags into the Irish Sea; Vaya con Dios, although since the film suggests that he returns from the services a changed man, hair-trigger violent in defence of his loved ones and contemptuous of wimpy authority figures, maybe the John in question is Rambo rather than Utah.

Lumbering all films with the obligation to be superior examples of their chosen form is a recipe for disappointment; but on the other hand why would you deliberately go for a low common denominator when the topic encompasses worlds within worlds? If the great wonder of genre films is the potential to contain nuance and resonance about things other than just their chosen characters — to be about other people than just these people — why not actually tackle the topic at hand, one with repercussions still more than audible over the horizon, and have at least a token crack at acknowledging the social and ethnographic bedrock? Do it right and the nuance will take care of itself. Witness The Warriors, a name being dropped often, whose understanding of tribal violence is deeper by a league than ’71’s, and in which Walter Hill could flood any scene with the air of 1979 New York just by opening a window. Demange can’t help that ’71 is a period piece, but has to take the rap for keeping all his windows firmly shut, as well as the calculation involved in blowing a young boy’s arms clean off to prove the film means business.

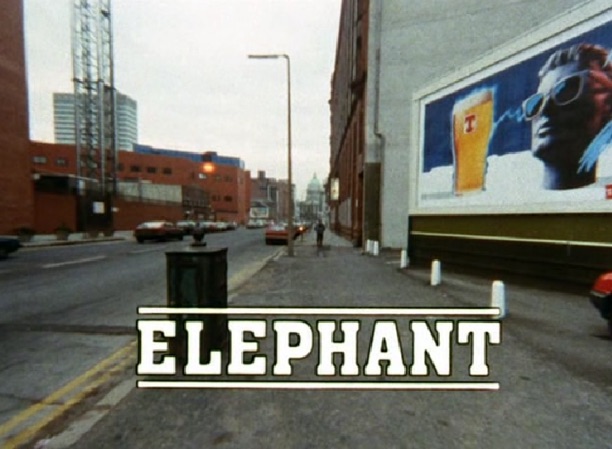

The acting isn’t a problem. The screen is going to like Jack O’Connell just fine playing heroes who are barrels of masculinity but also yelp when being sown back together without the aid of anaesthetic. A couple of the kids are magnetically hostile, especially Barry Keoghan as a murderous teen with the kind of face that Alan Clarke and Phil Redmond used to shove in front of the cameras before everyone else went to great lengths to shove them off again. But to mention Clarke is to acknowledge an option that ’71 declines to contemplate: putting in the hours to create a new grammar to speak the unspeakable, rather than borrowing someone else’s phrase book. Clarke found ways to approach the Troubles from the only directions that seemed to work for a functioning humanist facing a bottomless sectarian tragedy, including creeping up from behind and then yelling through a megaphone. The elephant in this room, as in most rooms, is Elephant.

The real pity of current commercial cinema isn’t when its wildly off-balance plan for ten years of superheroes squeezes human dramas of all varieties out of the equation, but when it wrings the ambition out of the ones that actually get made. Cultural irrelevance beckons, and it’s tough to get more irrelevant than that.